The Last Supper and the Meaning of Food

Reflecting on the Food Crisis in the Climate Emergency

As I write this, we are in Holy Week, the week in the Christian tradition where we move, with Jesus, to the cross, witness to the agony of his death on the cross, and wait, in the darkness, until Easter, when he will be resurrected from the dead into eternal life with God. In so doing, we, too, are promised eternal life with God.

In this week, meals – a certain meal – is given prominence. On Maundy Thursday, we remember Jesus’ last supper with his disciples, who were also his closest friends. It is told to us in scripture that, the day before Jesus was crucified, he shared a meal with them. As he did so, he blessed bread and wine. He held both the bread and the wine before them and said that when they eat these with one another, to do so in remembrance of Jesus and all that he represents. Symbolically, the bread and wine represent Jesus’ body; Jesus as the bread of life (from the Gospel of John), and the wine as a symbol of the blood he will shed in his dying. (The diversity of traditions within the Christian church place varying emphases on this latter symbol).

Jesus’ last supper has become the Eucharist, one of the sacraments in the Christian church in which it is believed that God is made present within a community of faith. Every time we celebrate communion, with bread and wine (or grape juice), we are remembering this final sharing of a meal between Jesus and his closest friends. Every time we celebrate communion, we are invited to that same table with Jesus and his disciples.

This past Sunday was Palm Sunday, when we remember Jesus entering Jerusalem on a donkey, in a parade of celebration that will, paradoxically, end in his death. In my home church that day, we celebrated communion together. In our modern time, the bread was cubes of gluten-free bread, and the wine in the individual cups was grape juice, (‘unfermented wine,’ from our Methodist roots). However communion looks in your tradition (or in the tradition of your friends, if you are not Christian), the essential meaning is the same: When we share a meal together, we are doing so in memory of Jesus’ self-sacrifice and gift of eternal life. When we share a meal together, we are doing so at that same table where his disciples sat, being nourished by the love and sustenance that Christ offers us.

Food is Central in Christian Tradition

Food, then, and the sharing of it, is central in Christian tradition. Of course it is: without food, every single one of us will die. Food is essential for every life form on Earth. Indeed, the food chain on the planet illustrates the truth of life, death and resurrection: to eat, something must die. In the complex web of life, living things die in self-sacrifice so that others may live. Whether we are talking about microbes, insects, plants, or animals, it is the same.1 We learn, through eating, that life is profoundly a gift, and that life and death are closely intertwined. Our eating can be the occasion, not just at Sunday communion or in Holy Week, to reflect on these truths.

However, it is Holy Week, as I write this. As it turns out, this year it is also the week of Passover in Judaism, and part of the month of Ramadan in Islam, This is a week in which food is an essential part of worship for followers of these three ancient faiths.

A Food Crisis in the Climate Emergency

So this is a perfect time to reflect on eating, on what it means for us as people of faith, and what it means right now, in the climate emergency. For while it is a holy time of year for us and our siblings in faith, the climate emergency continues, unabated. In the climate emergency, we have a food crisis. In the climate emergency, food – certain foods and the way they are grown – is contributing to the emergency itself. In the climate emergency, food is no longer treated as a gift, and leads to death more than it does to life.

Ecotheologian Norman Wirzba has written a cogent and powerful way of understanding eating and its implications in this time of crisis in his book Food & Faith: A Theology of Eating (2011). He develops an argument that, for Christians, food and eating can be best understood in terms of God’s gift and sacrifice. Interpreting the natural world as all of God’s beloved creation, he says,

Created life is God’s love made tastable and given for the good of another. The mundane act of eating is thus a daily invitation to move responsibly and gratefully within this given life.2

Yet, this is not how most of us are eating, today. As I have written about here, you can learn in the news, and Wirzba details in his book, the current industrial model of agriculture has moved us far away from experiencing the goodness of God in our eating. Currently, what we are eating is contributing to greenhouse gas emissions, species extinction and loss of land, the decimation of traditional ways of hunting, fishing, and growing food, and the starvation of millions of people around the globe, despite there being enough food to feed everyone. How food is being grown and processed is leaving farm workers impoverished; Indigenous peoples have been displaced from their lands; and the wide diversity of crops worldwide have been replaced with monocultures.

Most of us are eating food suspiciously uniform in appearance, from refrigerated shelves in brightly lit supermarkets, as well as in overprocessed and ‘fast’ forms. Most of our food does not come from the farm down the road, but from factory farms around the world. And, not only are millions of people going hungry in the global South, but in our world of easy and relatively cheap food (even with the current rise in food prices) here in the global North, there are food deserts and lack of access to healthy food in every single community. Wirzba says,

The character and pace of much contemporary life makes it less likely that people will perceive the mystery of food or receive it as a precious gift and sign of God’s sustaining care. Though information about food abounds, many of today’s eaters are among the most ignorant the world has ever known. This is because people lack the sensitivity, imagination, and understanding that come from the growing, preserving, and preparing of food.3

We have lost touch with how food is grown and preserved, how and who prepares it, to such an extent that the current global ways of growing and preparing food are leaving us starving or unhealthy from eating poorly, and is a major contributor to the climate emergency.

How do we make sense of this reality when we come to the communion table with Jesus? How do we make sense of this reality when we remember, on Maundy Thursday, that Jesus has asked us to break and share bread and wine together in remembrance of him?

How do we come to communion and break bread, knowing that many don’t have any bread? Knowing that the food we eat every single day is a big part of the problem of the climate emergency?

How can we come to communion and let ourselves be nourished by Christ, and begin to transform our relationships with food, so as to reduce greenhouse gases emissions significantly, and create food justice?

How can our sharing of bread and wine at Christ’s table lead us to sharing in the work of transforming our agricultural systems and healing the world?

When We Leave the Communion Table

When we leave the communion today, when we return from a Maundy Thursday service in which we have heard the story of Jesus’ last supper, and perhaps shared in a meal in our community, we need to go back to our own kitchens and change what we eat, and how we eat it. We need to go back to our supermarkets, and change what we buy, and how we prepare it. We need to go to our gardens, and learn or re-learn how to grow food, so as to have a better appreciation and connection with the Earth community that, literally, is the ground from which our food comes.

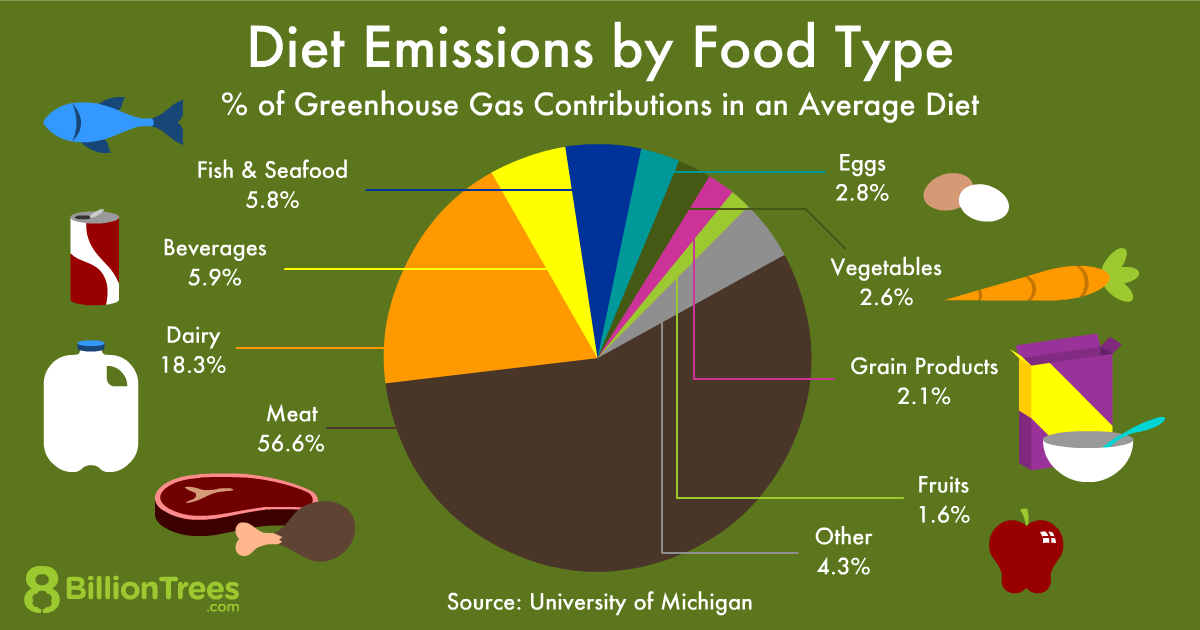

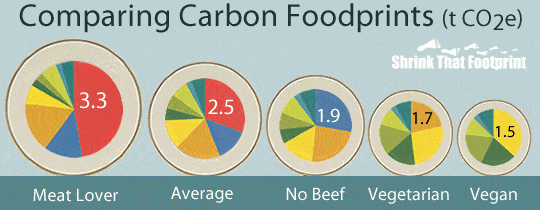

There is a lot of information available about the changes we need to make in our diets in order to secure a livable world, now and in the future. For example, we have to cut out the industry model of beef farming. Check out the graph below, to see what a difference it makes to simply remove beef from our diets. (I am not referring to small, sustainable beef farmers. They actually offer a model of what can be a sustainable, life-giving way of raising and eating meat).

It is too easy to forget what we need to do, and how we need to live, at suppertime. And of course, the relationship between our individual actions and the political changes that need to happen is complex. Yet, the single most effective thing we can do as individuals in the climate emergency, is change what is on our plates. The burning and clearcutting of the Amazon forests is a response to the rapacious demand for meat in the global North. If the demand is no longer there, the supply will dry up.

For those of us who are Christian, who follow the way of Jesus and eat at his table, we need to begin to think about what we eat, where it comes from, how it is made, and who makes it. We need to, prayerfully and with careful discernment, begin to rethink what we eat, where it comes from, how it is made, and who makes it.

Wirzba again:

Food is about the relationships that join us to the earth, fellow creatures, loved ones and guests, and ultimately God. How we eat testifies to whether we value the creatures we live with and depend upon. To eat is to savor and struggle with the mystery of creatureliness. When our eating is mindful, we celebrate the goodness of fields, gardens, forests and watersheds, and the skill of those who can nurture seed and animal life into delicious food. We acknowledge and honor God as the giver of every good and perfect gift. But we also learn to correct our own arrogance, boredom, and ingratitude.4

This Holy Week, I invite you to enter into the mystery and meaning of the bread and the wine, for what it says about who Jesus is, about creation, and about how we are nourished through God’s gifts and sacrifice to us. In turn, I invite you to then offer your own sacrifice of restraint at the table, effort in working for climate and food justice, and imagine a better, more abundant life for all.

Norman Wirzba, Food & Faith: A Theology of Eating (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). My ideas on food and eating are based on this book.

Ibid., xii.

Ibid., 3.

Ibid., 4.

Books for Transformation

Good Food: Grounded Practical Theology, by Jennifer R. Ayres (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2013)

In addition to Wirzba’s book, I recommend this book by Jennifer Ayres to you as well. Together, the books help to give a fuller picture of understanding how food and eating is deeply grounded in community, how the ecological and justice issues regarding food have caused harm, and how we can learn to ground our theologies and our faith practices within the practices of growing and eating food together. As a practical theology, this book offers narratives of the lived experiences of religious communities in the United States as they seek food justice. Ayres is calling for more communal initiatives to support local farmers and create fair food policies, which we need more than ever in our time.

Permaculture for the Rest of Us: Abundant Living on Less Than an Acre, by Jenni Blackmore (Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishes, 2015).

I love New Society Publishers; this Canadian company publishes some of the most compelling books I have found! This one is not new, but they recently highlighted it on their IG page. Since today’s essay is about food, I chose it as a hopeful text that can guide action – in this case, gardening action. Permaculture is an approach to gardening that seeks to model and live within the ways that ecosystems flourish. This book offers a way that we can do so even if we don’t live on a small farm, even within our city backyards! If you’re a gardener – or even if you’re not yet, but dream of being one – this book is for you.

Earth Community in Pictures

I am so grateful to members of this Following in the World community - you! - for sending me pictures and giving me permission to share them with you. I confess to being a little envious, too, when I look at Glen Wright’s pictures of his garden in Woodstock, ON, and one of the baby chicks that Jackie Schoemaker Holmes and her daughter are fostering. I want those flowers, and I want to hold those little fluffy babies!

Do you have pictures of the Earth community, where you live or visit, that you would like to share here (either with credit or anonymously)? Please send them to me at: jessica@jessicahetherington.ca.

Upcoming Events

I will be preaching at the following places in April and May:

April 23, 2023: Knox-St. Paul’s United Church, Cornwall ON

April 30, 2023: Trinity-St. Andrew’s United Church, Renfrew ON

May 28, 2023: Trinity United Church, Ottawa ON

I will also be speaking at the Antler River Watershed Region’s Spring Meeting in London, Ontario on May 13, 2023.

More details on all of these to follow. I hope that you can join me, in person or online!

The 2021 film Eating Our Way to Extinction is an exploration of the devastating impacts our eating habits have on the environment. It uncovers hard truths and addresses the most pressing issue of our generation -- ecological collapse. It's available for free at https://www.eating2extinction.com/