The Nonviolence of Discipleship VS the Violence of Climate Change

An essay on what a nonviolent discipleship of climate action means, and introducing two books on the violence of the climate crisis

To my new subscribers, thank you for subscribing and welcome to this community! If you’d like to know more about this publication or me, here’s my ABOUT page. And now let’s dive in…

The Violence of Climate Change: Book Recommendations

It’s been a long time since I’ve offered book recommendations to you, but it doesn’t mean I’m not reading! I’ve been catching up on the books I’ve shared here before and reading material that is related to my work, but less directly about climate change and the call to climate action.

We are in a climate and ecological crisis, and it’s all hands on deck... Subscribe to join a community of people of faith who care about climate action and find hope and encouragement at the same time!

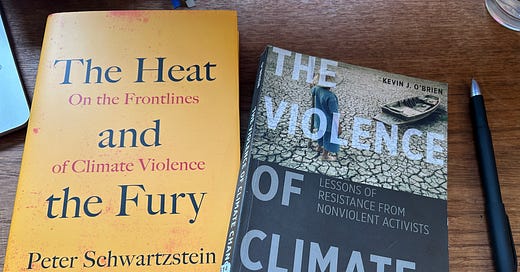

I’m currently writing a chapter on understanding the nature of Christian discipleship and how it relates to the call for climate action. In the section I share with you below, I am exploring the nonviolence of discipleship. In the course of doing so, it has meant learning more about the violence that is inherent in climate change. Here are two books I ordered recently to help me in my research.

The Violence of Climate Change: Lessons of Resistance from Nonviolent Activists, by Kevin J. O’Brien (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2017)

Kevin O’Brien is a Christian ethicist who explores the examples of nonviolent Christian activists who have come before us to see what their experiences can teach us in confronting the structural violence embedded in climate change. His ethical commitments in the book are fourfold: climate justice, learning from diverse social movements, engaging Christianity in inclusive conversation, and bringing “moral attention to both concrete action and abstract cosmological worldviews.”1 This book excites me because it draws on some of my favourite exemplars of radical discipleship, including abolitionist John Woolman, Catholic Worker Dorothy Day, and civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. I’m also introduced to the feminist reformer Jane Addams and union organizers Cesar Chavez. I haven’t finished the book yet, but what inspires me is how real-life examples are used to illustrate how theories of nonviolence and social ethics are lived out in specific contexts of time and place for others. I’m excited to learn what Woolman, Day, King, Addams, Chavez, and the thoughts of O’Brien himself can teach me about confronting the violence of the climate crisis with a nonviolent discipleship.

The Heat and the Fury: On the Frontlines of Climate Violence, by Peter Schwartzstein (Washington: Island Press, 2024)

This book is authored by an award-winning journalist who has covered issues of water, food security, and the relationship between climate and conflicts throughout the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere. Peter Schwartzstein has often put his own safety at risk in searching for the truth regarding how conflicts and the climate crisis intersect. In the book jacket that describes his being badly beaten, among other things, it says, “Yet these personal brushes with violence are simply a hint of the conflict simmering in our warming world.” The author explores the various dimensions of the climate crisis, such as water scarcity and drought, food insecurity and more, through specific case studies in Bangladesh, Syria, Nepal, Jordan, West Africa, and elsewhere. This is a secular analysis, without which Christian theology and ethics would be incomplete.

Have you read either of these books? What did you think?

The following is a section of a chapter I’m writing on what discipleship is and how it is manifested in climate action today.

The Nonviolence of Discipleship in a Time of Climate Crisis

When we explore the life and ministry of Jesus, we meet a radically nonviolent Jesus. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus gives us explicit directions for what a nonviolent life should look like. He also models that for us in how he interacts with everyone he meets in his ministry. Pacifist priest and author John Dear describes Jesus’ practice of nonviolence:

[Jesus] heals the sick and disabled, the victims of the culture of violence; he expels the demons of violence, in particular, our possessions and allegiance to empire and the culture of war; and he welcomes God’s reign of nonviolence by proclaiming it and making it real - by feeding the hungry and liberating the oppressed. His nonviolent resistance to violence confronts systemic dehumanization, such as when he defies sabbath laws to heal the man with the withered hand.2

Whether it is in conversation, breaking bread with outsiders, or challenging the religious and political authorities, Jesus demonstrates a creative nonviolence that is proactive and uncompromising. Jesus makes it clear to his disciples, and to us today, that loving our enemies and our neighbours must be radically nonviolent, too.

Jesus’ nonviolence did not end with his death on the cross. The cross itself is a symbol of both violence and nonviolence at the same time. While it represents the violent response of the state against Jesus and all he stood for, it also upholds the nonviolent resistance and continued love that Jesus expressed, even as he was being tortured, right to his very last breath. In his post-resurrection appearances, Jesus offered peace to his disciples, the peace of nonviolent love, mercy and grace.

This means, then, that our discipleship, modelled as it is on the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus, is nonviolent. A nonviolent discipleship is both personal and public,3 about how we live our individual lives and how we respond to the climate emergency in individual, social and political action.

To specify that discipleship is nonviolent is to recognize that we have to be very careful in how we answer God’s call so that our actions, however much we might intend to be nonviolent, do not cause violence to the other or the self. This is harder than it might appear, for just as it was in Jesus’ time, we are immersed in a culture of violence. The scourges of racism and xenophobia, sexism and misogyny, homophobia and variant forms of gender discrimination, classism that harms the poor and feeds upon human selfishness and greed; these and other forms of oppression foster and maintain the historical and current manifestations of colonialism and slavery everywhere around the world. War and militarism are rapacious and persistent expressions of violence, both against people and the Earth community itself.

It is within this culture of violence, of course, that the climate and ecological crisis is located. Violence manifests in the climate crisis in several ways in our world. For too long, violence perpetrated against the other-than-human world has been justified in the name of progress. The violence of clear-cutting forests, polluting the oceans, and burning fossil fuels is defended as necessary for doing business and pursuing progress.

Climate violence also includes the devastating ways in which global warming and other forms of the ecological crisis have impacted the poor and marginalized around the world, in the global south as well as in marginalized communities in the global north. The flooding of nearly a third of the country of Pakistan in 2022 killed more than 1700 people and led to widespread displacement, food shortages, and the spread of waterborne diseases. In Canada and the US, toxic waste dumps are located next to Indigenous and Black communities; this environmental racism has had a direct impact on the health outcomes for the people in those communities.

Climate violence also includes the violence that erupts in communities as a result of the climate and ecological crisis. Peter Schwartzstein, author of The Heat and the Fury: On the Frontlines of Climate Violence, says,

Across many of the world’s most vulnerable landscapes, climate change and other environmental furies are merging with other, better-understood destablizers such as corruption to undermine dozens of countries that can ill afford additional crises.4

Such violence against the planet and its vulnerable people has gone unnoticed, at least in the mainstream, and while we may see these examples and not recognize our role in them, we in the global north are directly complicit in such climate violence, through our consumption habits that fuel the climate and ecological crisis, and our complacency in holding industry and government to account and demanding policy changes related to fossil fuels and their funding, the plastics industry, and more.

The fact that we are immersed in a culture of violence, against the Earth community and its people, means that a nonviolent discipleship is harder than it may seem to live out. It’s perhaps ironic that nonviolence can be perceived as naive, passive, or weak, for it is none of those things.

Need to find encouragement and hope in this time of climate and ecological crisis? Want to support this eco-ministry that is international and ecumenical and have access to the full breadth of my work? With a paid subscription you’ll get more of the encouragement you need, find hope in this difficult time, and make this ministry possible!

Are you in paid ministry? I offer ideas and inspiration for your preaching, teaching, and pastoral care. You can claim the subscription as a continuing education expense.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Faith. Climate Crisis. Action. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.